A Functional Health Guide to Restoring Mobility

Executive Summary

Many people in their 40s and 50s begin to experience persistent back pain, joint stiffness, knee discomfort, hip pain, shoulder restriction, or a gradual loss of mobility that seems to appear without a clear injury. Daily activities that were once effortless — getting out of bed, climbing stairs, standing after sitting, walking long distances, exercising, or travelling — slowly become uncomfortable or even frightening.

Medical scans frequently reveal findings such as osteoarthritis, cartilage thinning, disc degeneration, spinal stenosis, facet joint arthritis, rotator cuff wear, or reduced joint space. The explanation is often brief and reassuring in intent: this is normal degeneration with age.

Yet this explanation rarely satisfies the lived experience of the individual. Many people intuitively feel that something deeper is wrong. They ask an important question: why does one person in their late 60s remain active and pain‑free, while another of the same age becomes progressively limited, medicated, and dependent?

This white paper explores that question through a functional health lens. Rather than viewing musculoskeletal degeneration as an unavoidable mechanical breakdown, functional medicine and functional health coaching view it as the visible outcome of long‑term biological imbalance across multiple systems of the body. Joint and spine tissues are living, responsive tissues. They regenerate, adapt, and repair when the internal environment supports them. When that environment deteriorates, breakdown gradually exceeds repair.

Using the seven‑systems functional health framework, this paper explains the most common musculoskeletal conditions affecting older adults, what functional and clinical research has revealed about their deeper causes, why pain management often becomes the dominant strategy in conventional care, and how this approach — while essential for symptom relief — may unintentionally allow root causes to continue unchecked.

Finally, the paper outlines how a structured functional coaching approach works upstream to restore the biological conditions required for healing, resilience, and long‑term mobility.

The Conventional View: “Normal Degeneration with Age”

Modern medicine has made extraordinary advances in imaging, diagnostics, surgical techniques, and pain management. Orthopedic care plays a critical role in ruling out fractures, serious pathology, instability, and acute injury. When pain is severe, reducing suffering is both necessary and compassionate.

However, musculoskeletal care is largely structured around structure. MRI and X‑ray imaging are designed to identify what has already changed — cartilage loss, disc narrowing, joint irregularity, bone spurs, or alignment alterations. These findings are real and measurable.

What imaging cannot explain is why those tissues lost resilience in the first place. As a result, clinical care often shifts toward managing pain and slowing progression rather than restoring biological repair. Painkillers, anti‑inflammatory medications, injections, physiotherapy, and in advanced cases surgery become the primary tools. For many people these provide temporary relief and are sometimes essential.

Yet over time, many individuals notice a frustrating pattern. Pain improves briefly, then returns. Medication doses increase. New joints begin to hurt. Fatigue rises. Activity decreases. Fear of movement grows.

This is not a failure of medicine. It reflects a difference in focus. When degeneration is already visible, the primary goal naturally becomes symptom control rather than root‑cause restoration.

Functional health complements this model by asking a different question: what biological conditions allowed degeneration to develop so extensively in the first place?

Orthopedic medicine is excellent at identifying structure. However, structure alone does not explain pain. Large studies show that many people with significant degeneration on MRI have little or no pain, while others with minimal findings experience severe disability. This disconnect reveals a critical truth: degeneration is not merely mechanical — it is biological.

Conventional medicine focuses on what has already broken. It rarely investigates why the tissue lost its ability to repair in the first place. As a result, patients are often offered painkillers, injections, physiotherapy, weight loss advice, or surgery, while the internal drivers continue unaddressed. Functional health looks upstream.

A Functional Insight: Degeneration Is a Process

Degeneration does not suddenly begin in the 40s, 50s, or 60s. For most people, it is the final stage of biological changes that began decades earlier. Subtle metabolic strain, low-grade inflammation, nutrient depletion, hormonal decline, chronic stress, poor sleep, reduced movement, digestive dysfunction, and weakening muscle signals quietly accumulate year after year. The body adapts — until its capacity to repair is gradually exceeded.

Cartilage, spinal discs, tendons, ligaments, and bone are not inert structures. They are living tissues that depend on energy, circulation, oxygen, nutrients, hormones, mechanical loading, immune balance, and nervous system regulation. When repair slightly exceeds breakdown, tissues remain resilient. When breakdown exceeds repair over many years, degeneration slowly emerges.This explains why many people cannot point to a single cause. There was no accident. No dramatic injury. Just life. From a functional perspective, the essential question is not what is damaged, but what systems stopped supporting repair. Degeneration is rarely the result of one problem. It reflects a convergence of system failures — which is why a seven-systems functional approach becomes essential.

Common Musculoskeletal Problems Seen With Age

Before exploring systems, it is important to make these conditions real for the reader. The following problems are among the most commonly seen in adults in their 50s or 60s.

Lower back pain and lumbar disc degeneration often present as morning stiffness, pain after sitting, or sharp discomfort with bending. MRI findings may show disc dehydration, bulges, or narrowing, yet pain severity often fluctuates independent of the scan.

Knee osteoarthritis typically begins with stiffness when rising from a chair, discomfort on stairs, or swelling after walking. Over time, cartilage thinning and inflammation limit confidence in movement.

Hip degeneration often appears as groin pain, reduced stride length, or difficulty rotating the leg. Many people assume it is muscular until imaging reveals joint changes.

Shoulder problems such as rotator cuff tendinopathy or impingement commonly arise without injury, leading to night pain, reduced reach, and weakness.

Neck degeneration and cervical spondylosis may cause stiffness, headaches, nerve symptoms, or arm discomfort.

Plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinopathy, and foot pain frequently accompany aging, especially in individuals with metabolic dysfunction.

Across all of these conditions, a striking clinical observation emerges: similar diagnoses often respond very differently depending on the person’s overall biology. This is where the seven‑systems functional approach becomes essential.

The Seven Systems That Influence Joint and Spine Health

- Metabolic and Energy System Dysfunction

Healthy joints depend on energy. Every repair process requires ATP, oxygen delivery, insulin sensitivity, and stable blood sugar. When metabolic health declines — through insulin resistance, rising glucose, or mitochondrial dysfunction — tissue repair slows dramatically. Cartilage cells become less responsive. Collagen production weakens. Inflammatory signaling increases.

Chronically elevated insulin and glucose stimulate inflammatory pathways that directly accelerate cartilage breakdown. This explains why joint degeneration is strongly associated with metabolic syndrome, abdominal fat, and type 2 diabetes — even in non-obese individuals. Joint degeneration is increasingly understood as a metabolic disease of connective tissue, not simply a mechanical one.

- Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation

Inflammation is essential for healing — when it turns off. Problems arise when inflammation becomes constant. Processed foods, excess omega‑6 fats, blood sugar spikes, gut permeability, poor sleep, chronic stress, and environmental toxins all stimulate inflammatory cytokines. These molecules degrade cartilage, weaken ligaments, and impair disc hydration.

Unlike acute injury inflammation, this form is silent. Blood tests may appear “normal,” yet tissue-level inflammation continues daily. Over years, this slowly erodes joint integrity.

- Gut and Digestive System Dysfunction

The gut plays a surprisingly central role in joint pain. Poor digestion, altered gut bacteria, and intestinal permeability allow inflammatory compounds to enter circulation. These activate immune responses that often target joints and connective tissue.

Many individuals with arthritis, back pain, or spinal stiffness also have long-standing digestive symptoms — bloating, reflux, constipation, diarrhea, or food sensitivities — that were never connected.

The gut-immune-joint axis is now one of the most researched areas in chronic musculoskeletal pain. If the gut remains inflamed, joints rarely heal fully.

- Hormonal and Repair Signaling Decline

As we age, anabolic hormones gradually decline. Testosterone, estrogen, growth hormone, IGF‑1, and DHEA all play vital roles in tissue repair. These hormones do not simply affect reproduction or energy. They regulate collagen synthesis, bone density, disc hydration, muscle strength, and tendon resilience.

When hormonal signaling declines — especially combined with poor nutrition and stress — the body shifts from repair mode to preservation mode. Degeneration accelerates.

- Musculoskeletal System: Loss of Muscle as a Protective Organ

Muscle is not merely for movement. It is one of the body’s most powerful protective systems. Strong muscles stabilize joints, absorb load, improve circulation, and release anti-inflammatory molecules during contraction.

Age-related muscle loss (sarcopenia) often begins in midlife, especially in sedentary professionals. As muscle weakens, joints absorb forces they were never designed to carry alone. The spine becomes unstable not because discs fail first — but because muscles stopped protecting them.

- Nervous System Dysregulation and Pain Sensitization

Pain is processed by the nervous system, not by joints themselves. Chronic stress, poor sleep, unresolved trauma, and persistent inflammation sensitize pain pathways. The nervous system becomes hyper-alert. Signals that were once harmless are now interpreted as threats. This explains why pain intensity often exceeds structural damage.

When the nervous system remains stuck in survival mode, healing signals are suppressed. Relaxation, breathing, movement confidence, and nervous system regulation become essential components of recovery — not optional extras.

- Immune System Imbalance

The immune system governs inflammation and tissue repair. With ageing, immune regulation often becomes confused — overactive in some pathways and underactive in others. This phenomenon, sometimes called inflammaging, contributes heavily to joint degeneration.

Instead of resolving micro-injuries, the immune system sustains them. Functional guidance focuses on restoring immune balance, not suppressing immune function.

The Functional Health Approach to Reversing or Slowing Degeneration

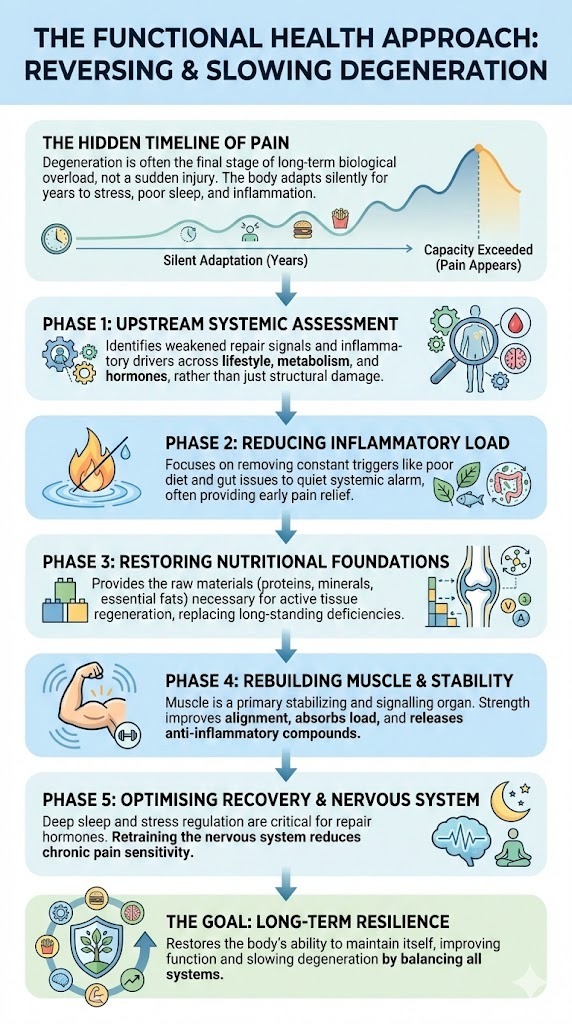

Most people who develop chronic back pain or joint degeneration did not experience a dramatic injury. There was no fall, no accident, no clear moment when something “went wrong.” Instead, the body adapted quietly for years — compensating for stress, poor sleep, nutrient gaps, metabolic strain, reduced movement, inflammation, and hormonal decline. It continued to cope until its capacity to adapt was finally exceeded.

By the time pain appears, the imbalance is rarely new. In functional practice, it is common to see patterns that have been developing for twenty or even thirty years before symptoms surface. Degeneration, in this sense, is not a sudden failure. It is the final stage of long‑term biological overload.

A functional health approach begins with this understanding. It does not promise miracle cures or instant regeneration. What it offers instead is biological logic — a way of understanding how the body actually maintains, repairs, and protects its tissues over time.

From a functional perspective, joints and the spine deteriorate not simply because of age, but because the systems that support repair are no longer functioning in balance. The essential questions therefore change. Rather than asking only what has worn out, functional guidance asks what has stopped working upstream.

Which systems are underperforming? Which repair signals have weakened? Which inflammatory drivers are continuously active? What is preventing healing from completing even when damage is mild?

Once these questions are answered, the work becomes methodical rather than reactive.

The first step is a system‑wide assessment. A functional coach looks across lifestyle patterns, nutrition quality, sleep depth, stress exposure, movement habits, digestive function, metabolic health, inflammatory markers, micronutrient status, and hormonal trends. No single data point explains degeneration on its own. Patterns across systems reveal where repair capacity has been compromised.

Very often, pain correlates not with the severity of structural findings, but with the degree of systemic strain. Poor sleep weakens repair. Blood sugar instability fuels inflammation. Digestive dysfunction amplifies immune activation. Chronic stress sensitises pain pathways. Muscle loss reduces joint stability. These relationships become visible only when the body is viewed as an integrated system.

The next phase focuses on reducing inflammatory load. This is not about suppressing inflammation, which is necessary for healing, but about removing the constant signals that keep it switched on. Food quality, meal timing, blood sugar regulation, gut integrity, sleep patterns, and environmental exposures are addressed together. In clinical experience, many people notice meaningful pain reduction at this stage alone, even before any structural change occurs.

As inflammation settles, attention turns to restoring nutritional foundations. Cartilage, tendons, ligaments, discs, and bone are metabolically active tissues. They require adequate protein, amino acids, minerals, essential fats, and micronutrients to regenerate. Long‑standing deficiencies are common in older adults and often go unnoticed for decades. When these raw materials are restored, the body regains its capacity to repair rather than merely protect.

Rebuilding muscle becomes a central focus. From a functional perspective, muscle is not optional for joint health. It is a primary stabilising and signalling organ. Adequate strength improves joint alignment, absorbs mechanical load, enhances circulation, and releases anti‑inflammatory compounds during contraction. Carefully progressed strength training, appropriate for age and condition, often produces improvements that imaging alone cannot explain.

Recovery signalling is then addressed. Deep sleep, circadian rhythm alignment, and stress regulation support the hormones responsible for tissue repair. Without adequate recovery, even excellent nutrition and exercise fail to translate into healing. Rest is not passive in functional biology; it is when regeneration occurs.

Equally important is nervous system regulation. Chronic pain frequently persists not because tissue damage remains severe, but because the nervous system has learned to remain in a state of threat. Functional guidance incorporates breathing practices, pacing, reassurance through safe movement, and gradual exposure to rebuild confidence. As the nervous system returns to a state of safety, pain sensitivity often decreases significantly.

The final goal is long‑term resilience. The objective is not short‑term symptom relief, but restoring the body’s ability to maintain itself. When metabolic health improves, inflammation quietens, muscle strengthens, sleep deepens, digestion stabilises, and stress responses normalise, degeneration slows and function often improves beyond expectation.

This is how functional health changes the trajectory.

What Happens When the Root Causes Are Not Addressed

When pain becomes the dominant focus, people often reduce movement. Muscles weaken. Insulin sensitivity declines. Weight increases despite eating less. Sleep quality deteriorates due to pain or medications. Inflammatory load rises further.

Non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs may reduce pain, but long‑term use can impair gut lining integrity, increase cardiovascular risk, and reduce nutrient absorption. Cortisone injections can calm inflammation temporarily, yet repeated exposure may weaken connective tissue repair. Pain medications may blunt symptoms but also reduce activity levels, accelerating muscle loss.

None of this occurs because treatment is wrong. It occurs because symptom management alone cannot reverse systemic imbalance.

Over time, the original biological drivers — inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, hormonal decline, gut permeability, nervous system stress — quietly intensify. This is why many people experience a cycle: one joint improves while another worsens. Pain shifts location. New diagnoses appear.

How Functional Guidance Changes the Trajectory

Functional coaching does not replace medical care. It works alongside it. Modern medicine excels at diagnosis, imaging, and acute intervention. Orthopedics addresses structure. Physicians manage disease and risk. Functional coaching focuses on the internal terrain that determines whether tissues continue to break down or regain the ability to rebuild.

By translating complex biology into practical daily actions, functional guidance helps individuals understand how everyday habits influence healing. People move from passive acceptance of aging to informed participation in their recovery. This restoration of agency is often as important as any biological change. Through comprehensive assessment, patterns become clear. Blood sugar instability explains tendon and joint pain. Poor sleep explains impaired recovery. Digestive inflammation explains flare-ups. Muscle loss explains instability. Chronic stress explains pain amplification.

Interventions are not random, but layered logically. Nutrition stabilises metabolism and reduces inflammatory signalling. Gut support restores immune balance. Strength training rebuilds protective muscle. Sleep reactivates repair hormones. Nervous system regulation reduces pain sensitivity and restores movement confidence.

As systems recover, many individuals experience not only less pain, but better energy, balance, sleep, and overall resilience — outcomes that scans alone cannot measure.

Final Thoughts

Ageing does not have to mean progressive pain or shrinking freedom.

While structural changes may occur over time, functional decline is not inevitable. When the body’s systems are supported together — metabolism, inflammation, digestion, hormones, nervous system regulation, nutrition, and movement — the body often regains a surprising capacity for repair, adaptation, and strength, even later in life.

Back pain and joint degeneration are rarely isolated orthopedic problems. They are signals that the body has been under strain for a long time, adapting quietly until its reserves were exhausted. When those reserves are rebuilt, healing becomes possible again — not always dramatic, but meaningful, steady, and life-restoring.

Perhaps the most important shift is not only biological, but psychological. People move from passive acceptance of aging to informed participation in their health. From managing decline to understanding what their body truly needs.

Functional health guidance exists to support that transition. Working respectfully alongside modern medicine, it helps uncover the deeper story beneath the scan — and restores the conditions that allow movement, confidence, and independence to return.

For many, this is where a different chapter of aging quietly begins.

References

Attia, P. and Gifford, B. (2023). Outlive: The science and art of longevity. New York: Harmony Books.

Lieberman, D. (2013). The story of the human body: Evolution, health, and disease. New York: Pantheon Books.

McGill, S. (2016). Back mechanic: The step-by-step McGill method to fix back pain. Waterloo: Backfitpro.

Starrett, K. and Cordoza, G. (2015). Becoming a supple leopard: The ultimate guide to resolving pain, preventing injury, and optimizing athletic performance. Las Vegas: Victory Belt Publishing.

Bickman, B. (2020). Why we get sick: The hidden epidemic at the root of most chronic disease — and how to fight it. Dallas: BenBella Books.

Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers. New York: Henry Holt.

Vasquez, A. (2016). Integrative orthopedics: An evidence-based approach to improving musculoskeletal health. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Maffetone, P. (2015). The big book of endurance training and racing. New York: Skyhorse Publishing.

About Mathew Gomes

Functional Health, Nutrition & Longevity Coach

Mathew Gomes is a Functional Health, Nutrition & Longevity Coach helping busy professionals reverse early health decline before it becomes disease. Trained in Functional Nutrition Coaching (AAFH) and certified in executive coaching (ICF, EMCC), with an engineering background and MBA, he brings systems thinking and strategic clarity to health restoration.

Shaped by senior leadership experience and a personal health crisis, Mathew uses functional assessment and targeted testing to identify root causes and coordinate personalised nutrition, metabolic repair, strength training, nervous-system regulation, sleep and recovery. He works alongside doctors for diagnosis and medication while building resilient, sustainable health—so clients regain energy, focus and confidence without guesswork.

Disclaimer

This white paper is provided for educational and informational purposes only. It is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, prevent, or provide medical advice for any disease or health condition.

The author is a Functional Health, Nutrition and Longevity Coach, not a medical doctor. The content presented reflects a functional, educational perspective on health, lifestyle, nutrition, and risk factors, and is designed to support informed self-care and productive conversations with qualified healthcare professionals. Nothing in this document should be interpreted as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment from a licensed physician or other qualified healthcare provider. Readers should not start, stop, or change any medication, supplement, or medical treatment without consulting their prescribing clinician.

Individual responses to nutrition, lifestyle, supplements, and coaching strategies vary. Any actions taken based on this information are done at the reader’s own discretion and responsibility. If you have a medical condition, are taking prescription medication, or have concerns about your health, you are advised to seek guidance from a licensed healthcare professional before making changes.